- Home

- Jackson Galaxy

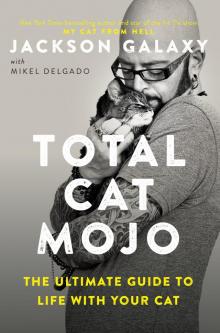

Total Cat Mojo Page 6

Total Cat Mojo Read online

Page 6

The Whiskers

The main function of whiskers is to provide tactile information to a cat. But they also provide us with some information about how relaxed or aroused a cat is.

Left: Soft whiskers

Right: Forward-pointing whiskers

A relaxed cat usually has soft whiskers that are pointing out to the side, while a fearful or defensive cat might flatten the whiskers against the sides of the face as another way of becoming “small.”

Forward-pointing whiskers indicate a cat is trying to get more information, since those whiskers will detect air movements and objects. The more forward facing the whiskers are, the more attentive the cat is. Forward whiskers could indicate that a cat is about to attack, perceives a threat, or is just plain interested, so, as always, context is important.

No single behavior or posture happens in a vacuum, so remember to consider the big picture as you evaluate your cat’s state: Is she relaxed on the couch? Staring out the window at another cat? Crouched under your bed? You also have to look at the whole enchilada—of course, that entails what’s coming from the body, tail, eyes, ears, and whiskers, along with vocalizations, but also what’s coming from the territory, the other inhabitants, even the time of day. If there’s one thing I’ve learned in translating cat language, it’s the importance of context.

Body Postures

Unlike some animals, cats don’t have clear appeasement signals, or submissive body language that says “please forgive me.” (Probably because such a thought would never occur to them!) But this communicative limitation impacts a cat’s ability to engage in conflict resolution. How can cats function in this way?

Go back to the timeline and look at how recently cats have been social—not just with humans but with each other. The ancestor cat was not a social species, and these days, domestic cats often resolve conflict through avoidance and defensive behavior, and maintain bonds through a group scent and signals like the tail up. But understanding the communicative challenges will help you understand why cats sometimes have difficulties with each other.

Cats who are upset usually take one of two routes. They can go bigger, with hair on end and an expanded posture—i.e., the classic “Halloween cat.” These cats are on full alert and may be willing to defend themselves if necessary. Straight legs, a puffed tail, and an elevated butt is a cat who is purely on the offense, essentially saying “Bring it on, I’m ready.”

Cats who make themselves smaller, on the other hand, are trying to appear unthreatening. Their ears are back, their shoulders are hunched, and they are crouching: everything is tucked in. If they get backed into a corner they will attack if they must, but that would be a last resort.

Lest you think cats are always defensive around each other, let’s be clear—cats do have friendly full-body gestures, namely rolling and rubbing. Body rolls happen when a female is in heat, but male cats roll, too. Many cats roll in response to catnip, but they also roll in the presence of other (usually older) cats. Much like the tail up signal, rolling seems to be a way to signal “I’m friendly and unthreatening.” Rolling is rarely seen during antagonistic encounters between cats.

Belly up is a play solicitation in kittens, although in adults, it could serve as a defensive posture, as their teeth and all four paws are readily available for protection in this position. Those belly-up adults are generally not interested in starting trouble, but it can indicate a willingness to defend themselves, if necessary. See the “Cat Hug” later in this chapter for more about belly-up cats.

Yawning and stretching are good signs that your cat is feeling mellow. A relaxed cat will often lay with all paws folded under the body, in what is often referred to as the Meatloaf position. All of the cat’s weapons are tucked away, and there’s no immediate intention to run or defend.

The Sphynx is another relaxed pose, where the front legs are extended in front of the body. A truly content cat will be in one of these poses with very “drowsy” eyes.

Both of these poses must be distinguished from crouching—a tense position, where a cat might be hunched over or partially propped up on the front legs. Often you will see tension in the face, or tight blinking of the eyes. In cats, this is usually a sign of pain. Because cats hide pain so well, it is important to pay attention to these subtle behaviors.

Is Your Cat Annoyed?

Many guardians think that their cat bites “apropos of nothing,” but most cats give many warnings, although these warnings may be subtle. Some cats may walk away or turn their back to you, and that is their way of removing themselves from an interaction. Or maybe you’re seeing some tail swishing, or back twitching. A paw swipe is also a warning, as if to say: “I don’t like this and you need to respect that. Next time there might be teeth or claws.”

See “Overstimulation” in section 4 for more on warning signs of irritation.

Cat Daddy Dictionary: The Cat Hug

When a cat goes belly up for you, we call this the Cat Hug, because often it’s the closest you will get to a cat actually hugging you. To fully appreciate this, you must understand the genetic experience of being a prey animal. By exposing their belly to you, they are essentially saying: “I am 100 percent vulnerable to you right now. You could take your claw and eviscerate me down this line from my throat to my groin and essentially tear me open. It is the most vulnerable part of my body, and I am flipping over and showing it to you.” Just like the body roll, it is a message of trust.

Now, is this an invitation to put your hands on your cat’s belly? No! Again, if you respect their protective instinct as a prey animal, and understand what every bone in their body is telling them, then you will appreciate the Cat Hug from a safe distance (unless you’ve already established a clear and comfortable relationship with your cat that would include belly rubs). Also, as mentioned, because this position is sometimes used as a defensive one, it’s very easy for cats to suddenly bite or scratch if they perceive your hand near their belly as a threat.

HOW THE CAT COMMUNICATES AS A SOCIAL ANIMAL: OLFACTION AND PHEROMONES

As stalk-and-rush hunters, cats don’t use their sense of smell much for hunting. In contrast to dogs, who might track prey for long distances, cats follow prey only a short distance.

But smell is critical to how cats relate to each other. Their sense of smell is approximately fourteen times as strong as ours, and it’s important to remember that olfactory information talks straight to the part of the brain that is key to emotions and motivations, such as anxiety and aggression.

Cats can also detect pheromones with their vomeronasal organ (VNO—also called the Jacobson’s organ). Pheromones are special chemical signals that reveal information about sex, reproductive status, and individual identity. You might have seen your cat make an “open mouth sniff” or grimace, which is called the Flehmen response. This behavior is a sign that a cat is taking in those pheromones (usually via the urine of other cats). From that Flehmen response, they know who has been around, when they’ve been around, and possibly even their emotional state. Are they a familiar cat? Are they an intruder? A female in heat? An intact male? Are they stressed out? This information can be used to help cats avoid contact and conflict with other cats.

Urine spray elicits a lot of sniffing in cats, especially if it is the urine of an unfamiliar cat. But strange urine doesn’t necessarily cause cats to avoid an area—it’s not necessarily a “keep out” sign.

Pheromones

Cats can leave pheromone messages through glands on their cheeks, forehead, lips, chin, tail, feet, whiskers, pads, ears, flanks, and mammary glands. Rubbing these glands against objects or individuals leaves the cat’s scent behind. The functions of all of the different pheromones are still Mojo Mysteries, but researchers have identified the functions of three facial pheromones.

One pheromone (F2) is a message from tomcats saying “I’m ready to mate.” The pheromo

ne F3 is released during cheek or chin rubbing on objects, and helps cats claim ownership of their territory. Finally, F4 is a social pheromone to mark familiar individuals—human, cat, or other. F4 reduces the likelihood of aggression between cats and facilitates the recognition of other individuals.

How cats rub to mark can tell you a little bit about their emotional state. Cheek rubbing is generally a sign of confidence, and “head bonking” against you is a sign of “cat love.”

Scratching is another way for cats to mark their turf, but sometimes cats will also release alarm pheromones when scratching.

Urine marking is both a sexual behavior and a response to territorial changes (such as new animals or objects). While urine marking is a completely normal feline behavior, in some ways, it is the antithesis of facial marking; it’s the Napoleonic response to territorial anxiety.

WHAT MAKES CATS Raw is what unites them all; the ties that bind, however, only tell half the story. As we complete our exploration of all cats, it’s time to start digging deeper to discover what it is that makes your cat one of a kind. Now, let’s get to know your companion better. Much, much better.

5

The Mojo Archetypes and the Confident Where

AT THIS POINT I hope I’ve painted a good picture of cats as a whole. All cats. How they—in the context of their Raw life, outside, free from the confines of your home—use the tools that evolution has graced them with to accomplish their daily objectives. The almost reflexive pursuit of these goals creates a cat springboard of sorts into the deep pool of Cat Mojo. Now it’s time to start thinking about how we can take this all-cat info and bring it to our cats—whether that means using the Raw Cat to bring out the best in our companion cats, or finding out how our home territory can maximize their mojo and improve our daily relationship with our cats.

THE MOJO ARCHETYPES

Truth be told, I was never a big fan of “types,” of reducing anyone to a handful of characteristics. As a matter of fact, that’s why I’ve ditched the term “cat behaviorist” after my name. Talk about reductive! It makes it seem as if all I do is look at a four-legged bag of symptoms and arrange the puzzle pieces so that “it” becomes a perfect, connect-the-dots collection of “behaviors.” Wouldn’t you be just a little peeved if your therapist referred to herself as a “human behaviorist”? Feels more than a little cold, right?

That said, I unfortunately don’t have the time to get to know every cat to the degree that I would like. In the span of a few hours, I have to get through the handshake, the observations of environmental and family dynamics, challenge line exercises, diagnosis, homework assignments, and wrap-up. With Cat Mojo as the end result I want to promise every animal and human client, I’ve found that underneath every individual cat I meet, there is a claim that he or she has staked along the mojo spectrum. Without pigeonholing, I have found that guardians and I both benefit from identifying where their cat is and where they want to get to on that spectrum.

Cat Mojo begins with confident ownership of territory; but by the time we’ve done our work to raise their mojo bar, it’s not just about ownership, but pride; and it’s not about territory, but home. Knowing where your cat falls on the mojo spectrum gives us a clearer sense of what our goal looks like. And so I created the Mojo Archetypes. Allow me to introduce you to the Mojito Cat, the Napoleon Cat, and the Wallflower.

The Mojito Cat

You’ve got new neighbors, and a couple of weeks after they move in, they invite you to come over—a bit of a housewarming, get-to-know-you type of thing.

You knock on their door and you are immediately met by a level of exuberance that knocks you off your feet a bit. Your new neighbor greets you with a huge smile, welcoming you by name and offering a warm hug as if you’ve known each other for years. You are being hugged with one arm because, you notice, the other hand is holding a tray of drinks.

“Mojito?” she asks. “We’ve got a few different flavors here. This one is more lime-y, that one has a little more cucumber. These have salt on the rim and those don’t.”

You pause, still somewhat in a state of shock. She laughs, seeing that you are a bit quiet—but she just hands you one of the drinks and leads you gently by the elbow inside.

“Let me show you around. . . .”

Your first stop is the fireplace, where you’re shown pictures on the mantel of vacations, birthdays, weddings. Your hostess stops to pick up an antique picture, lovingly running her fingers over it as she talks about the bond she had with her grandmother. She cries a few tears, wipes them away . . . and the tour continues.

You are taken through every nook and cranny. And, incredibly, there seems to be history in every one of them, and through this show and tell, you find yourself invested in this unfolding story.

Wait a minute . . . you stop in your tracks . . . these people just moved in here? It looks—and feels—like they’ve been here for years. And it’s not just the arrangement of things—the mementos, the furniture, even magnets and to-do lists on the fridge—it goes deeper than that. . . . It’s a vibe. You are just awestruck that two weeks ago, the moving trucks left this house, and today . . . it’s a home.

Your hostess with the mostest, you notice, is not running around, trying to impress, nervously throwing coasters under your mojito. You realize that this sense of ease comes from the fact that she’s not here to impress. She’s not interested in the status that would come from being “perfect.” She just wants to know you, and she wants you to know her. There is no artifice in this home. And the escape plan that you had in your back pocket? It stays there. Why? Because you want to stay here.

Now—imagine if this human were a cat.

Then, as soon as you walk into the home, this cat walks right down the center of the room, tail held high, chest up. Ears are forward to explore, but not flicking in all directions as if trying to pick up clues about this incoming being. Eyes are also forward, but to greet, not to check the periphery for escape routes. Instead of presenting a tray of drinks, the Mojito Cat begins to do figure eights between your legs, and those of anyone else who crosses his path. You reach a hand down to say hi. He takes your outstretched fingers and pushes them to his forehead, his cheeks. Simultaneously he is inviting contact with a stranger, allowing pleasure from that contact, and marking you in a confident way, turning you into his human scent soaker. As you walk into the family room, he climbs to the third level of the cat tree that stands near the door, showing you how he surveys the domain, displaying pride in what is his. You walk into the kitchen, he scoots ahead of you and digs into his dinner as you settle into a conversation. The scratching post in the living room gets a workout when you and the Mojito Cat pass through again. And with every stop on this “tour,” you are head butted and cheek marked . . . and finally, as you settle on the couch for conversation, he falls asleep—either on or next to you.

The Mojito Cat lies at the center of our Mojo-meter. He is a true north of confidence. He has nothing to prove; he is Tony Manero strutting through Brooklyn. His love for, pride in, and unquestioned ownership of his territory are what makes it his home. The Mojito Cat is marked by this characteristic: he loves his environment so much that he just wants to share it. This is evidenced by his actions in his surroundings and with the beings who populate that environment. And that, folks, is what true Cat Mojo looks like.

The Mojito Cat occupies the center; he gives us a target to aim for, and a planet for our other two archetypes to orbit around. While Mojito is so confident he wants to show off his home to you, offering to share its riches, our other two cats are marked by their deep insecurities. Instead of exhibiting grounded ownership, our other cat archetypes are either petrified that you’re going to take away what they have, or feel that they aren’t worthy to have ever owned anything in the first place. Enter our second archetype.

The Napoleon Cat (a.k.a. the Overowner)

I grew up in New York City

during a time when gang activity was so rampant that it felt normal. My parents taught me where I would be safe to travel and where I would not be.

After falling asleep on a bus one day, I found myself overshooting home by about twenty blocks. I cautiously got off the bus and went to cross Broadway to wait for the next bus heading back toward home. As I crossed to the downtown side of the street, I was stopped by . . . a kid; I mean he couldn’t have been older than I was at the time, around thirteen. I don’t remember the name of the gang he was a part of, but I knew he was a member. Why? Well, to begin with, he wore a denim vest, frayed at the shoulders, with the name of the gang on it, both on the front and the back. He put himself squarely in my path, puffing out his chest and folding his arms.

“You know where you are?” he said, his face inches from mine. “Let me tell you. . . .” And he motioned to a huge “tag,” the name of his gang in white paint on the side of a brick building.

I remember being profoundly confused as to what he actually wanted from me. I assumed he had some kind of weapon on him because I was taught to believe that, but he never brandished it. He just stood in front of me, eyes narrowed to slits and his entire being ready to take action.

This kid clearly didn’t want to kill me, but with every passing second he was, at the very least, growing more and more impatient with my lack of recognition. He wasn’t trying to bar entry onto their turf (unless, of course, I was a member of a rival gang)—he just wanted me to acknowledge that this belonged to “them.” It struck me, through my vaguely adrenalized state, how young yet intimidating he was. His arms-folded posture, his “bowed up” torso, and all of the elements of gang wardrobe—together, they created a uniform of fear that had been mastered by so many kids back then.

Total Cat Mojo

Total Cat Mojo Cat Daddy

Cat Daddy